One of the buzz-words in business schools is data analytics or, in an accounting school, accounting analytics. But what exactly is ‘accounting analytics’? How is it different from existing tools and disciplines such as ‘statistics’, ‘computer science’, ‘machine learning, ‘Big Data’, or ‘managerial accounting’? In this post I will disentangle this emerging field. This is a first crack at this issue — I will continue to edit as the field (and my understanding of it) develops.

Accounting Analytics Defined

Accounting analytics, in a nutshell, is the examination of Big Data using data science or data analytics tools to help answer accounting-related questions. Let’s break that down further.

The Emergence of Big Data

The first piece of the puzzle is `Big Data.’ Big Data is different from previous forms of data in terms of volume, variety, and velocity: There is a lot more of it, it comes in a variety of structures and formats, and it is updated and produced quickly. Any of the following might be considered sources of Big Data for an accounting analytics project:

- social media data

- web search data

- journal entries

- transactional data (e.g., customer transactions)

- call centre transcripts

- store videos, web cams, etc.

- online customer reviews

- XBRL

- proprietary databases

- websites

- IoT devices

- image repositories

- sensor data

- public data (crime, health, education, etc.)

- media/journalism

- weather forecasts

- company emails

- company disclosures

There are lots of good articles and blog posts out there on this point. The key to recognize is that Big Data goes beyond just social media data.

The Emergence of Data Science

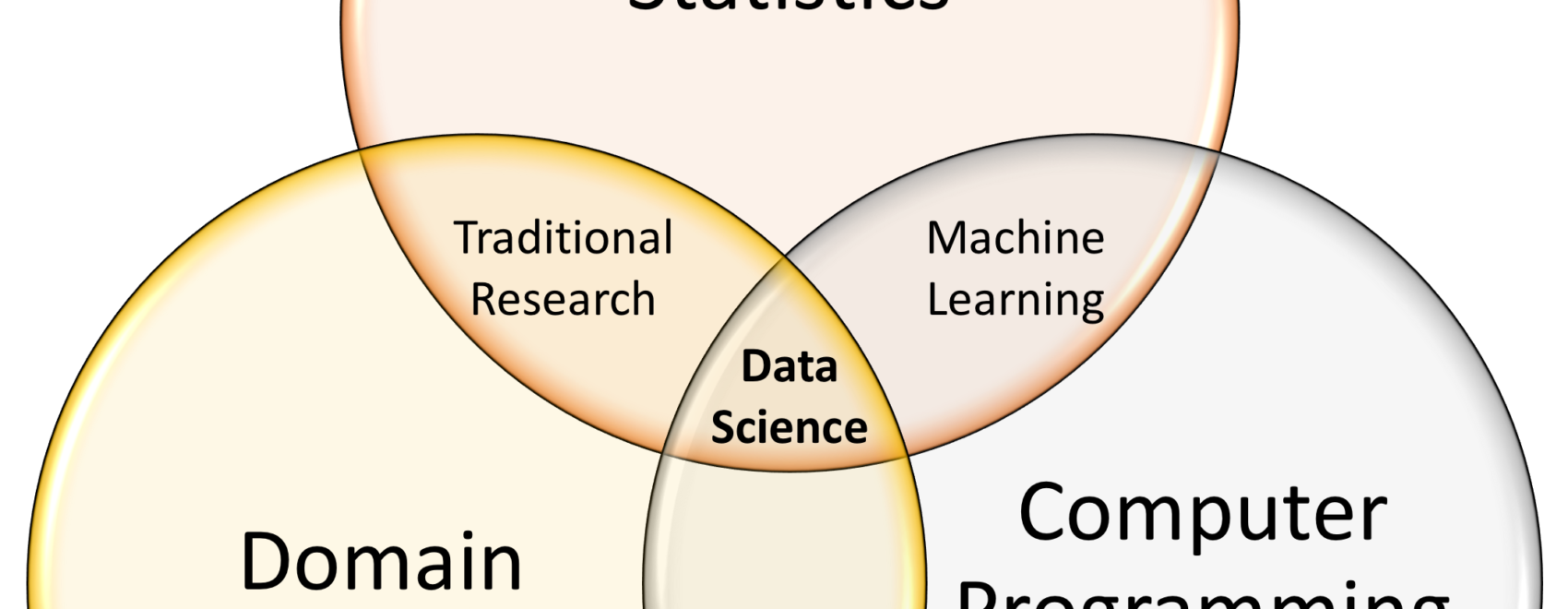

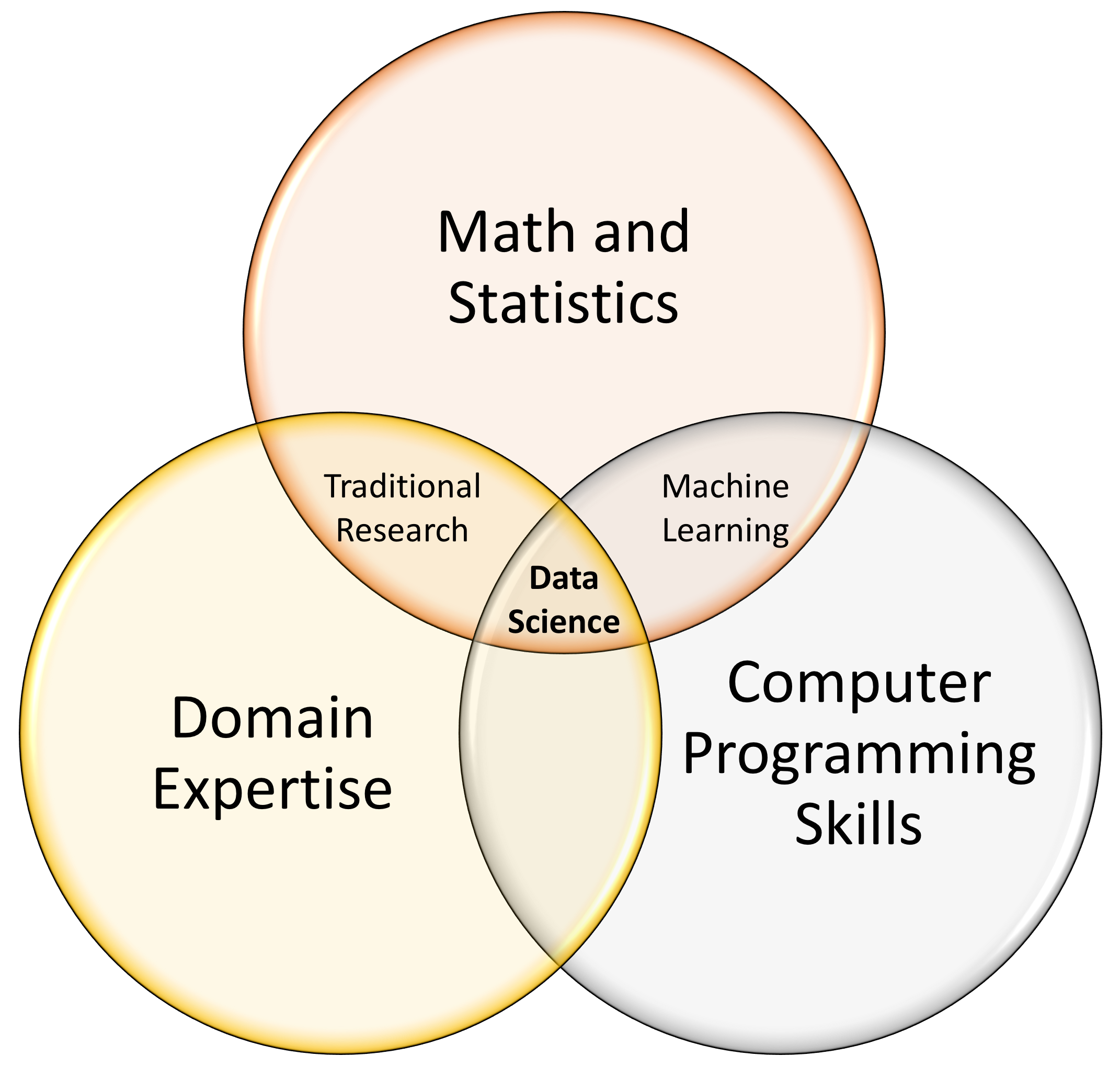

The second piece of the puzzle is `Data Science.’ Data scientists examine Big Data using a combination of programming skills, statistical skills, and domain knowledge to answer relevant organizational or societal questions.

Data science has emerged in the past decade with the emergence of Big Data and the concurrent development of readily accessible sophisticated computing tools. At its core, data science is a field, or perhaps an approach, that lies at the intersection of three things: 1) computer programming, or ‘hacking’, skills; 2) mathematical and (especially) statistical skills; and 3) domain expertise.

Programming skills are needed to help access and download Big Data, to `wrangle’ the data into a usable state, and to write programs that can run sophisticated machine learning and related algorithms. Statistical skills are needed to ensure the appropriate research design methodologies are followed and statistical techniques applied; without this, your projects findings will not have validity. Finally, domain expertise is needed in order to identify questions that are worth answering. In accounting analytics, domain expertise is knowledge about the business and industry along with understanding of the accounting information system.

Data Analytics vs. Data Science

There does not appear to be a consensus on the distinction between ‘data science’ and ‘data analytics.’ You can refer to a number of articles and blog posts that attempt to describe the difference. For example, some think of data analytics as a narrower sub-field of data science. To my mind, however, the two terms are more or less synonymous. Accordingly, accounting analytics can be thought of as the use of data science/data analytics techniques to answer accounting-related questions.

Generic Data Analytics Tools

A well-rounded data scientist needs to have a broad ranges of tools and techniques in her toolkit. We might think of these as encompassing four stages of the process: 1) data gathering, 2) data wrangling, 3) data management, and 4) data analysis.

Data Gathering

Hacking skills are indispensable for accessing and downloading certain types of Big Data — particularly social media data. Here the data scientist will need to become familiar with application programming interfaces (APIs). I have written a blog post on how to set up access to the Twitter API, and there are lots of other resources out there.

Data Wrangling

Data wrangling or ‘data munging’ is a critical data analytics skill. Once you have the data you then need to get it into a usable format. This might involve generating ‘pivot tables’ in Excel or PANDAS or R, or aggregating a time-series dataset to the daily or weekly or monthly level, or generating a series of new variables (aka ‘feature engineering’). And it might involve all of these things. Big Data are often unstructured data, meaning they are lacking pre-defined fields (aka ‘columns’ or ‘variables’) and linkages across databases. I don’t want to devote too much time to this issue as you’ll find plenty of resources online. The key takeaway is that data wrangling is something any social scientist or other type of researcher is familiar with — with Big Data there are just additional challenges in terms of scope and nature of the issues you’ll be dealing with.

Data Management

Data scientists should have familiarity with database management. There are lots of options out there, ranging from traditional relational databases such as SQL to ‘noSQL’ databases such as MongoDB. In my own research I have recently leaned toward the MongoDB approach, but the data scientist may not have a choice. For this reason a solid understanding of both major approaches is helpful.

Data Analysis

Once you have the data in usable format and you’ve found a question worth answering, you then need to analyze the data. There is a huge range of techniques for analyzing the data. In my training as a social scientist and then accounting scholar, I was trained to think of two broad sets of techniques — descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. Examples of the former are the mean, mode, median, and standard deviation, and are used to describe the data that you’re working with. To help deliver answers to a given research question, we then turn to a wide range of more advanced statistical techniques, including ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, logistic regression, negative binomial regression, etc.

Data scientists avail themselves of all these techniques in addition to a much broader range of tools. This is due in part to the rapidly developing field of computer science as well as the different types of questions data scientists are asking (it is a long story, but the crux of the argument is ‘prediction vs. explanation’).

Here the data scientist will be familiar with all of the ‘buzzwords’ — artificial intelligence, deep learning, machine learning, text mining, sentiment analysis, clustering, and more. Again, I don’t want to reinvent the wheel, so any number of articles out there can explain these tools and how they are applied in data analytics.

Accounting Analytics

OK, by this point I hope you have a better sense of what ‘data science’ is. What you may not see is how this is practically applied in the field of accounting analytics. Here I have a somewhat different take than other articles and blog posts I’ve read. Most of them seem to categorize data analytics and/or accounting analytics questions into a ‘descriptive’ (what is happening) vs. ‘retrospective’ (backward-looking) vs. ‘prospective’ (what will happen) framework. While accounting analytics is certainly used for description, retrospection, and prediction, I prefer to approach this field differently. Namely, I focus on two main research questions: 1) measurement and 2) finding relationships.

Measuring Accounting Concepts

A first set of accounting analytics questions are designed to help measure an accounting-related concept. Accounting is inherently a ‘measurement discipline’, but accounting information systems are not equipped to deliver insights into all variables of interest. Here’s a concrete example. Let’s take an intangible asset such as a company’s brand community. The company has built this intangible asset itself so it is off the books — it will not be seen on the balance sheet and thus will not automatically be measured.

As shown in the figure below, it is critical that the accounting analytics practitioner first recognize that the notion of ‘brand community’ exists at the conceptual level — we have no solid concrete measure of it. Instead, we need to examine a range of different indicators that, collectively, can help us measure this concept. The figure below shows four variables, or indicators, that could be examined to help infer the strength of the company’s brand community.

None of these indicators in isolation would suffice. It is only by ‘triangulating’ our findings that we are able to make any valid inferences. And it is only by employing data analytic techniques that we are able to gather and wrangle these data.

Most accounting students are not trained in separating the conceptual from the measurement level, yet it is a critical piece of the puzzle. It is one of the core competencies of the data scientist’s training in statistics and methods.

Finding Relationships

The second type of accounting analytics question addressed is the search for relationships between one variable and another. For example, the accounting analytics practitioner might be interested in what behaviors predict fraud. This is the search for the relationship between some set of ‘X’ behaviors and a ‘Y’ outcome variable (fraud). This is an ‘accounting’ analytics question because of the accounting-related variable fraud.

Similarly, the analytics practitioner might wish to segment job applicants into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ applicants. The analytical tool might involve a clustering algorithm, and as in the above example, ‘under the hood’ the analyst is using a variety of variables help separate promising from less promising applicants. In other words, the exercise involves finding patterns built concerning the relationship between a bunch of “X’s” and an outcome variable “Y” (job applicant quality).

I’ll give one last example here. The figure below shows an accounting-related variable sales. Sales data would already be gathered in the accounting information system. Here is where many accountants would stop. Accounting analytics, however, brings something new to the table. Namely, accounting analytics is not only interested in measuring sales but in relating sales to other variables. In other words, the accounting analytics practitioner is keenly interested in seeing what other variables can predict the increase (or decline) in sales. This is the search for relationships. Where data science enters the picture is in two ways. One, inferring relationships is inherently a statistical or methodological pursuit, and training in statistics is not typically a forte of the accountant. Two, the data employed is often non-financial in nature. Big Data is commonly used and thus data science tools are a necessity.

As shown in the figure, the accounting analytics team is interested in predicting future sales for the company. To help answer this question, the team gathers an array of financial data (not shown) as well as non-financial data, including the strength of the online brand community, the number of five-star Amazon reviews, an assessment of the company’s CSR and sustainability initiatives, weather patterns, and customer complaints. Once these data are gathered and wrangled, operational measures are developed and then statistical analyses are applied. Based on these analyses the team will have answers to what the strongest predictors of sales performance are.

These are just a few examples. There is a huge range of questions that could be answered using accounting analytics. The key is these questions involve at least one ‘accounting’ variable and rely on Big Data and data analytics tools.

What The Typical Accountant Needs to Know

The great majority of accountants (and accounting students) are not going to become data scientists. What all practitioners should learn is data literacy. They need to know understand what types of questions can be asked (measurement and finding relationships), what types of information are available (Big Data), and what types of analyses can be run. In short, the typical accountant does not need to know how to do data science but does need to understand what data science is. They should, in Cornelissen’s (2018) words, “speak the language of data.” Being ‘data literate’ will help you and your team make better requests of the data scientists. As seen in the Henke et al. (2018) article linked below, a recent buzzword points to a new career path for those who are literate in data analytics — the ‘analytics translator.’

Further Reading

This is intended to be a relatively brief overview of the rapidly emerging field of accounting analytics. I hope this article has provided a useful overview.

Accounting academics and practitioners are rapidly building knowledge of this emerging field. In an update I will add some key academic articles for further reading. For now, I refer you to four brief Harvard Business Review articles.

- Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson. Big Data: The Management Revolution, Harvard Business Review, October 2012.

- Hugo Bowne-Anderson. What Data Scientists Really Do, According to 35 Data Scientists., Harvard Business Review, August 15, 2018.

- Jonathan Cornelissen. The Democratization of Data Science., Harvard Business Review, July 27, 2018.

- Nicolaus Henke, Jordan Levine, and Paul McInerney. You Don’t Have to Be a Data Scientist to Fill This Must-Have Analytics Role., Harvard Business Review, February 5, 2018. (Also available here)